No one knows why he chose Nottingham.

Arthur ‘Artie’ Scattergood had it all. His parents – my great, great grandparents – were textile merchants. They lived in a big house, on a grand Georgian square, in one of the nicest part of London.

And one day, it’d all be his. The house, and the factory, and the money. The life.

But Artie didn’t want it.

Why, we never knew. When he rocked up at Bestwood Village in 1920, he had no friends, no prospects, and no reason for being there. Maybe he’d taken the first train out of St. Pancras; maybe he just closed his eyes, and pointed at a map.

Whatever the plan was, Artie worked hard. He made himself a life—a life of his own, for the first time. He got a job at Bestwood Colliery. He found himself a woman, and a home. And soon enough, he found himself a football team.

My great grandmother—he loved her without condition. That all took care of itself.

But with Forest, things were a bit more complicated.

Because Artie had a temper. We think that was one of the reasons he left London in the first place—probably, why he needed to leave. And Forest just seemed to bring out the worst in him.

On a match day, my great grandmother always hid the good plates. Just in case. It was a seven-mile walk back from the City Ground, and she had no way of finding out the score. But she knew when to expect him back.

And just from how he opened the door, she’d know what’d happened.

Artie Scattergood – you wanted some, he’d give it ya

If Forest had won, Artie would eat his tea, and go straight back out, and things were fine. But if they’d lost… he was monstrous. He’d break things—crockery, ornaments, furniture. Anything he could get his hands on. I always think of Gordon Ottershaw, in Ripping Yarns; I think of her, sat calmly at the kitchen table (in my head, she’s always knitting) as the shards of timber and porcelain whistled past her head.

He’d shout, and he’d fling, and he’d rant about how bad they’d been. About how they weren’t even trying. The pain of it—something a woman couldn’t hope to understand. And she’d tell him – calmly, forever knitting – to go back out, and to get it out of his system.

So that’s Artie would do. He’d grab his coat, and his hat, and he’d head off to his local. Off to look for a fight.

He was a short, gobby Cockney, drinking in a pit town. He never had to look far.

—

“They’ve always been the same. They’ll beat Arsenal one week, and lose to Salmon Tin Rovers the next.”

When Forest first started ruining my weekends, that was all she’d ever say. My nan – Eileen – was in her seventies by then, and hadn’t been to a game in years, but something in her voice told me it’d be that way forever. A weariness—a kind of audible shrug. What are you gonna do? It’s what they are.

The forties: that was her era. Billy Walker’s team. She was stationed on an anti-aircraft battery in Scotland, and when she came home on leave, she’d head to the City Ground—head straight for the sounds and the smells of a happier, safer place. She was twenty-one years old, and she had a chunk of shrapnel wedged so deep in her leg, they never got it out.

In between the bombs and the sirens and the sleepless nights, football was something normal to come back to. In a world gone mad, it was one of those things that still made a little bit of sense.

She always went to Forest games in her uniform. When they saw her coming they’d clear a path, right to the front of the Main Stand, and it made her feel good. In a man’s world, she suddenly mattered. They all looked at her differently—the miners, and the factory workers. In that uniform, she had their respect.

Right up until the end of her life, she talked about that team and those times in forensic

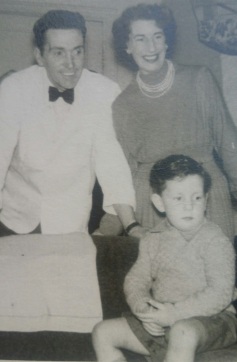

Eileen, her husband Arthur, and my dad – 1960

detail. The games, and the goals, and the squad that for fifteen years, never seemed to change. Bill Lambton in goal—always, Billy Lambton in goal.

And the lad that broke his leg: she was especially fond of that story. She always seemed to bring it out in the middle of a Sunday roast.

“You could hear it go from the other side of the ground, like a gunshot. They carried him right past us. It was awful. His leg was in a worse state than China.”

And then the same footnote, every time, as she gnawed on a big bit of crackling.

“You knew it was bad, because he was screaming. And men didn’t scream back then.”

—

Last Saturday, I marched. For a pokey little football club, beloved by four generations of my family—I marched.

Not for what Forest have become – it was nothing to do with that, or them – but just for being there, across the years.

For being there, when a young man in a new town was looking for something to call his own.

For giving a tired young woman a break from the Luftwaffe.

For being a thing to put your finger on, when people ask you what you are; for being the longest love that most of us will ever know.

For being Forest, ever Forest. For being the glue between me, and Artie Scattergood—two

Artie and me – April, 1981

men separated by a hundred years, but bound by a bit of grass and a clunky old football ground, crouched beside a river. The home of a strange and special club that’s filled in the blanks, all through our lives: speaking for us, and about us.

It’s easy to follow a Liverpool, or a Chelsea, or a Barcelona. That’s just common sense, and it doesn’t explain anything about you. It’s like saying that your favourite band is U2, or the Foo Fighters: there’s nothing wrong with it, but it’s just so very obvious.

When you tell – or told – people you were a Forest fan… that was different. Like Paul McGregor said:

“It meant something—it meant a certain moral structure, a certain DNA. It was almost like saying, ‘I’m one of the good people in the world’.

Forest stood for something. If you supported them, that’s who you were.”

And that’s why we marched. For that idea, and for the men who helped to forge it: for Roy Dwight, and Ian Storey-Moore, and Robbo, and Stan.

For the cast of a hundred others, and for all of the stories. Whether it was the love passed on to us, or the steps we’ve stood on, or the windswept night time journeys back down Britain’s motorways, with all the bus windows bricked in. For you, and for your travels; for my dad, sleeping beneath a Union Jack flag on a pile of sand, outside Hauptbanhof station. Explaining to confused Germans with his Tommy Cooper-hands exactly how and why Nottingham Forest were magic; smuggling himself onto the wrong ferry at Ostend, because he’d been stupid enough to promise his wife that he’d be back home – definitely – by Saturday morning.

For the games that meant nothing to anyone but you, and the thousands of friendships that have bloomed from a tinpot provincial football club. One that’s plugged away for all this time, as a whole new world grew up around it.

If that’s not worth celebrating, what is?

Now more than ever, Forest need reminding of what they’re meant to be; to us, and to the rest of the world. This football club that seems to have lost itself entirely; that’s been pissing on its own feet for too long, and wasting everybody’s time. A club that’s getting harder and harder to like, let alone love.

Last weekend, we came together to remind them that it’s not about trophies, or wealth, or any guaranteed glories; that simply, it’s about giving a few thousand people something to lose themselves in, at the end of a long week. Whether that week was waged in a pit, or behind a gunsight, or even a PC: it’s all any of us want. Something that we can believe in, without worrying about financial legislations, and court summons, or any other crisis that’s got naff all to do with eleven red-shirted men kicking a ball around.

The worries, and the fretting: there’s enough of that in real life. It’s not why we do this.

Forget what Andy Reid says, or Cohen, or Lansbury, or any other cheerleader wheeled out to let us know just how fine everything is. We’ll be the judge of that, and we’ll say when it’s fine. Because we know what Forest are meant to be. What they’re meant to look like, and how it’s meant to feel.

After all these years, and all this time—we know. By instinct.

And that’s why we marched. That’s why we set up a Supporters’ Trust, on Thursday night. To help bring back to life a football club that stands for something—one with a certain moral structure, and a certain DNA.

Simply, to get our Forest back.

It’s what Artie and Eileen would have wanted.

All marched out – April, 2016

Phil, absolutely brilliant as ever. Everyone who is involved running or playing for our club should have to read this, and then sign to show that they have understood it.

LikeLike

Bless you Tony. Very kind words. I wouldn’t hold my breath on that one, though…

LikeLike

As ever, a wonderful piece. Thank Phil

LikeLike

That is simply superb.

LikeLike

Very kind of you to say so Chris – thank you for taking the time to read it.

LikeLike

Cracking read , we are different that I truly believe

LikeLike

Don’t stop believing it mate – it’s true. And that’s why we have to work hard to make sure no one at Forest forgets it.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Passing Time and commented:

The best thing I’ve read about football in a long time. For those who share my despairing love of Forest, or other football clubs with similar histories, you’ll understand. For those who don’t get it, read this, and try. Forest ’til I die.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, this is wonderful. It’s moved me to tears, as someone who came to Notts in the late 60s and found a football team, and long after the glory years made my Sheffield-born son support them too. I still do believe in miracles… at least I try to…

LikeLike

Thank YOU. It’s wonderful that you’re able to relate so much to Artie’s experiences, arriving in a new city yourself 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was a good read and I can relate to it as far back as 1968 being a season ticket holder for over 40 years but not any more because the modern footballer does not care about the fans anymore and it’s not just forest it’s everywhere you look overpaid under worked tired playing on average 3 games every 2weeks ask the European cup winning sides if they were tired no they cared about the club and would argue if told they could not play in games not a lot more I can say only I don’t enjoy going to matches any more so choose to stay away don’t know if you’ll post this but it’s how I feel

LikeLiked by 1 person

Outstanding – and full of the soul that’s sadly becoming absent from our club. Forest did used to stand for something, and it was all about trying to do the right thing, in the right way, even if it didn’t always work out. Let’s hope we can get that back somehow.

LikeLike

I reckon someone made the players read this at half time last night.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A beautiful read – thank you for articulating what the real fans feel.

It was a privilege to hold my Ian Storey-Moore banner on the march! Fans for life!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was you was it Roland? Nice one. My wife Mel got some fantastic pics of you on the march!

LikeLike